Focal points of action // Paradigm shifts

[WORK IN PROGRESS]

This article is a perhaps quixotic attempt at answering the eternal question: “What should I do with my life?”

It seems difficult to overstate the scale of the issues (outlined here) facing both humanity and the biosphere as a whole: from climate change to biodiversity loss, and from increasing economic inequalities to the rise of authoritarian governments, global trends are hardly cause for optimism.

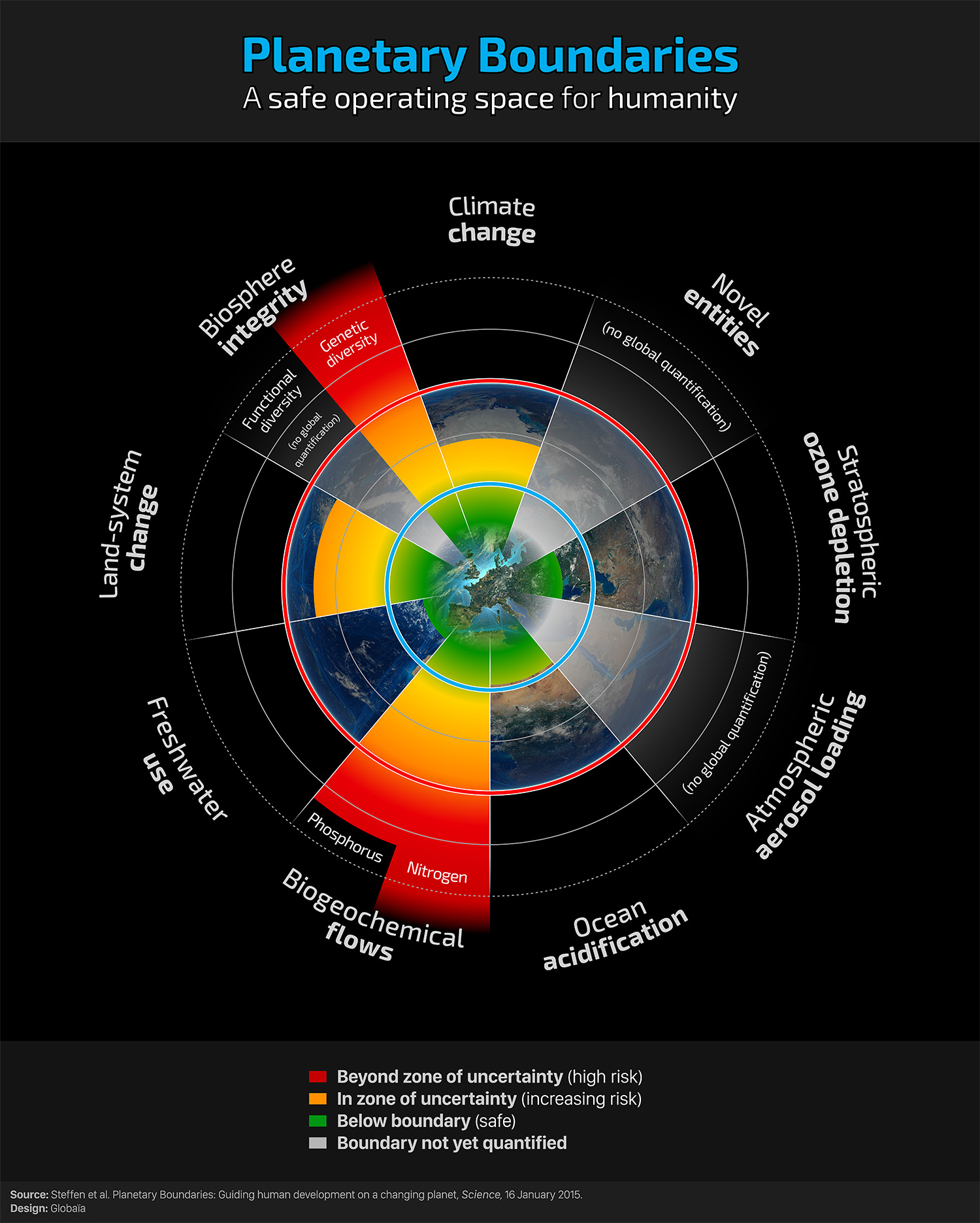

I tried to outline some essential points of concern on this page. More recently, I have also (thanks to the indispensable George) come across the hugely stimulating concepts of “planetary boundaries,” and of “doughnut economics.” As a brief summary, the first notion identifies 9 “boundaries” out of which we should absolutely refrain from pushing the planet, for fear of reaching tipping points that would trigger extreme, irreversible, and unpredictable change at the world scale:

As we can see from this graph, the authors of this concept (Johan Rockström and his team) estimate that we have already moved out of the “safe” zone (the blue circle) for at least four of these earth-system processes: climate change, biosphere integrity, land-use change, and biogeochemical flows (mostly flows of nitrogen and phosphorus, in which agriculture and other forms of organic pollution play a critical role). In the case of the last two boundaries, we have even entered a phase of extremely high risk.

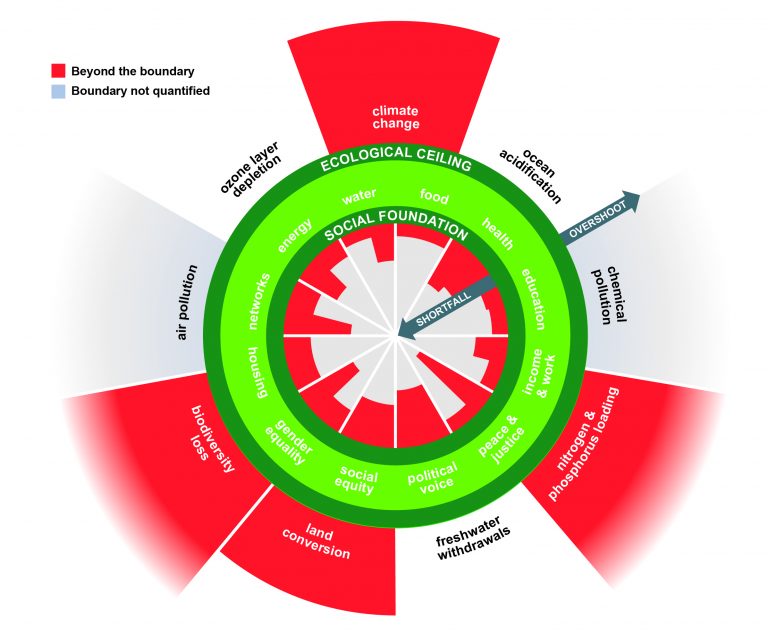

Kate Raworth’s notion of “doughnut economics” takes planetary boundaries as a basis, but adds to them a “social foundation,” measures of essential human deprivation:

Graphic by Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

In sum, our goal as a species should be to remain within the safe green zone—within our “ecological ceiling,” but above a common “social foundation.”

I find this framework particularly useful and thought-provoking.

And yet, each of the parameters mapped out on this graph represent an infinite complexity of flows and inter-related phenomena on the world scale. Given the immensity of the challenge, how should one go about deciding where to act, and what to do with one’s limited time?

Of course, it is possible to set such “mega-issues” as climate change or social equity as one’s focus, from a macroscopic perspective, and to make it one’s mission to fight this phenomenon on a global level—within such large organisations, for example, as Oxfam, the WWF or UNEP. Thousands of people do precisely this, and I am sure they find their work to be profoundly meaningful and rewarding.

On the other hand, it is probably just as commendable to act in a local fashion, and try to make the world a better place by first making one’s home, one’s neighborhood, and/or one’s city a better place—the Transition network, to name but one example, has shown just how potent grassroots organizing (alied to the power of the Internet) can be.

I find both those approaches necessary to make any sort of real progress toward a world that is fairer, more humane, and especially more respectful of the natural ecosystems that we are a part of. However, I also feel that neither is really satisfying, as far as I am concerned.

To put it briefly, I am skeptical as to whether global organizations or their grassroots counterparts are really best suited to bringing about change at the scale—and especially, the speed we need right now. This is but a gut feeling.

I am willing to believe that institutions like the various UN bodies, or huge NGOs like the WWF have been instrumental in contributing to solve some of the issues mentioned above; but is it at all possible for such vast organisations to avoid the pitfalls of bureaucracy, and to successfully deal with each and every one of the very diverse issues they chose to tackle? Anecdotal evidence from conversations with friends working in such institutions seems to generally point to a negative answer.

Likewise, I am quite confident that local action can be very efficient in tackling important social or environmental issues, or simply in providing people from a certain area with healthier, happier lifestyles, bringing them closer to nature and giving extra meaning and beauty to their lives. These are invaluable rewards in themselves. Nonetheless, one need only consider the very marginal and fragmented nature of such initiatives, even in such a relatively free and wealthy country as France for example, in which people enjoy a high level of education overall, to realize the limits of the “power of example” (see this book review, in French, for further details); as for the Transition movement, it may be growing, but a decade after it started, its scale still remains minuscule worldwide. In other words, while such local actions are far from negligible, I cannot but doubt the strength of their impact on a national level, to say nothing of the world scale.

These criticisms in no way negate the importance of these various ways of organising. Believing that only a certain form of social and political action should take place would be naive and foolish.

However, in view of the above, as regards the way to answer my own question at the beginning of this article, I am feeling increasingly interested in organisations (or action networks) that would correspond to the following criteria:

- Big enough, to exert a maximum positive impact on the largest scale possible…

- … But still “lean and mean” enough—i.e., not hampered by their size in terms of general efficiency and responsiveness, for reasons of hierarchical structures and other bureaucratic constraints for instance; this requires innovative means of organising and communicating, probably in a very decentralised way.

- Intensely focused on addressing the root causes of a certain global crisis, on various geographical levels.

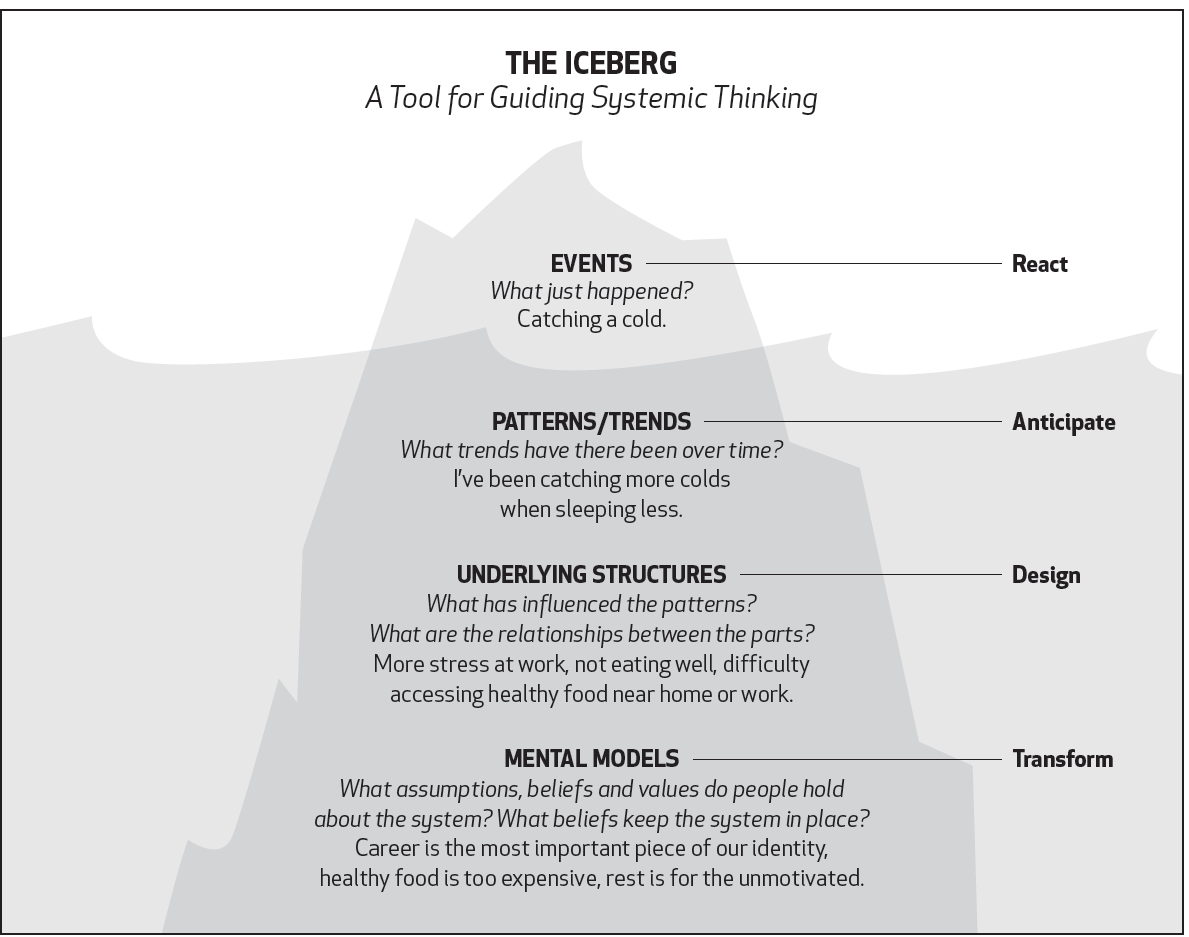

This last point is, to me, especially crucial. What I refer to as “root causes” would correspond to the third and fourth levels of the well-known “iceberg model” used in systems thinking:

(Source)

In a word, this mode of thinking involves tackling the deepest structural basis of the issue under consideration. For example, simply forbidding people to cut down trees in the Amazon Basin would only address deforestation patterns, and the efficiency of this kind of policy might only be very shallow. But making European cattle only consume feed made from sustainably-produced soy might considerably decrease the incentive for farmers in Brazil to cut down the forest to plant soy—especially if they can rely on more sustainable livelihoods—thus dealing with some underlying structures of the problem. But one could go even deeper, and go about converting Europeans to a mostly vegetarian diet, and educate Brazilian farmers and their children to the benefits of ecosystems services, to change the mental models that are primarily to blame for the fact that people even cut trees to raise cattle…

***

So, let’s imagine we want to find (or create) organisations that tackle the root causes of some of the major social and ecological issues that the world faces today. The next problem is that these issues are so overwhelmingly vast and far-reaching, in both their causes and their consequences. Can any single organisation take on the root causes of “climate change,” “biodiversity loss” or “world poverty” as a whole? Even reducing one’s scope to only certain particularly prominent structural elements of such issues appears challenging to me; the sheer magnitude of the problem seems to make its perimeter hardly compatible with the requirements I raised above, in terms of organisation size, efficiency, and focus.

(Again, this is all just intuition and guesswork here, I haven’t read any comparative studies of organisational efficiency relative to organisations’ size and scope; I might be wrong.)

From this starting point, it might make sense to reduce the scope of the “major issue” under consideration, so as to make it more actionable. But how to do this and yet keep the global scale of the “doughnut” in mind? In other words, can one identify a limited number of major “leverage points” which, if solved, might synergetically help combat several problems at once?

In the remainder of this article, I will try to do just that. What I present here is a set of five “issue nexuses,” for lack of a better word. Each of these elements, in combination with the others, plays a fundamental role in causing (or exacerbating) the major issues mentioned at the beginning of this article. They are interconnected and self-reinforcing. Bringing one down will only solve part of the global equation; but if each of them can be tackled with maximum strength and efficiency, then many root causes of such diverse issues as climate change, biodiversity loss, deforestation, world poverty or wealth inequalities will be addressed in one fell swoop.

What confirms my opinion that these elements are so fundamental is that they could also be read as fundamental paradigms which mankind should phase out of, in order to make any substantial progress:

- Economic growth is absolutely necessary;

- It is normal that a small class of people should hold in their hands most of the wealth and power in the world;

- Our society cannot survive without fossil fuels;

- Intensive agriculture as we know it is the way to go;

- It is mankind’s role to dominate nature, and to extract materials and energy from the planet, ad infinitum.

This is but a tentative list, for my personal use. Any feedback and criticism would be most welcome.

1. Economic growth

(Or: “If it doesn’t grow, we’re screwed”)

Economic growth is vital to the stable functioning of modern (industrialized) societies as we know them. Without it, everything starts to fall apart (public services, employment, general well-being, etc.). Therefore, all mainstream economics places its pursuit at the heart of its models.

Historically, it has indeed been thanks to economic expansion (and to the ongoing technological innovation at its core) that societies have been able to achieve higher standards of living, including better education, healthcare, nutrition, etc.

However, this historical expansion has been carried out at an increasingly high social and environmental cost worldwide. Social, because the need to find the resources and labor necessary for production have generally led to immense human exploitation and suffering on behalf of the owners of the means of production; and environmental, because economic growth is by definition a process of ever-increasing production and consumption of goods and services, and therefore of raw materials and energy. The extraction of materials and energy has led to deforestation, to soil, water and air pollution, and of course to vast emissions of greenhouse gases, among other impacts.

Although some have raised the possibility that economic growth could be somehow “decoupled” from material and energy consumption (i.e. every extra unit of GDP would require less materials and less energy), this decoupling has never taken place as of yet.

A case can be made for the continued focus on economic growth as a fundamental pursuit of society within many “developing” countries, in which a large share of the population still lives in poverty. But in the case of “developed” societies, where (1) the fundamental needs of the vast majority of people are met on a stable, everyday basis, (2) the average GDP per capita (or any equivalent measure) has already reached levels beyond which any additional unit does not bring more satisfaction/happiness, and (3) any additional unit of GDP entails considerable social and/or environmental impacts around the world: the pursuit of economic growth should no longer be necessary—or at least, it should lose its central position within macroeconomic models. On the contrary, in such countries, it is high time for the already accumulated wealth to be better shared among people, and for social safety nets to be extended to cover everyone in need, so as to attain the highest possible levels of general prosperity.

Therefore, a new “steady-state” economics is needed, which would enable societies to remain stable and prosperous without the need to rely on every-increasing production and consumption—and perhaps even to accept more “simple” or “sober” lifestyles, with less emphasis on material accumulation.

2. Post-democracy

(Or: “It is normal for a few people to own the same wealth as half the world—and to use it to rule us all”)

Since the end of the 1970s, and especially since the Thatcher and Reagan administrations, neoliberalism has led to an increasing democratic deficit in the world—especially in the US, and in global institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, but also in many other countries into which this ideology was “exported” with or without the consent of local people (from Chile in 1973 to Russia in 1991 or Greece in 2015).

Due to the rise of financial capitalism and to labor deregulation, once-powerful labour unions have grown weak, and the workforce atomized, while global firms emancipated from national states have appeared and spread thanks to trade globalization. In order to attract or keep foreign investments in the territories they represent, politicians now have important incentives to partner up with these firms, thus forming a global dominant class controlling business, states, the media, and international institutions. These elites have also overwhelmingly benefitted economically from the neoliberal enterprise. For example, between 1993 and 2012, the top 1% richest people in the US saw their incomes grow by 86.1%, while the incomes of the bottom 99% only grew by 6.6%. Most of the wealth created in advanced economies since the 1980s has been captured by the rich, which has not been of great economic benefit to countries as a whole. [1. Stiglitz, J. Globalization and Its Discontents. 2003]

As for citizens, they have been turned into consumers, passive observers of the political spectacle, whose votes no longer challenge the status quo—except through the election of populist, xenophobic leaders.

The effects of this “post-democratic” trend are far-reaching. The increasing difficulty for ordinary citizens to exert any meaningful control over political processes ensures that the globalized elites may continue pursuing their self-serving goals, generally in a short-termist manner that does not take into account the public well-being, nor the impact of their activities on the planet as a whole (which is exponentially higher than that of poorer populations) [2.“The biggest source of planetary-boundary stress today is excessive resource consumption by roughly the wealthiest 10 per cent of the world’s population, and the production patterns of the companies producing the goods and services that they buy.”— Raworth, K. A safe and Just Space for Humanity – Oxfam Discussion Paper, 2012]. This self-enrichment process increases economic and social inequalities, leading to a world of “haves” and “have-nots”; faced with the situation, the latter group is becoming more and more receptive to politically or religiously extreme messages, which foreshadows possible new conflicts.

In a word, neoliberal globalization has had very negative impacts on the world, on social, political and environmental levels. A paradigm shift towards more meaningful (as opposed to merely formal) democracy is absolutely necessary to avoid further increase of inequalities, unchecked environmental destruction, and the resurgence of conflicts and authoritarianism.

3. Fossil fuels

(Or: “Make the World Great Again”)

The industrial civilization has been largely built on the exploitation of cheap and abundant fossil fuel reserves, especially coal and oil.

However, the threat of runaway climate change now makes it necessary to stop using such energy sources, and accomplish a complete transition as soon as possible to renewable sources of energy. At least 80% of all fossil fuel sources currently confirmed to be in the ground must remain there to limit global warming to 2ºC.

Besides considerably lowering the human impact on climate change, transitioning to renewables is also likely to bring about many benefits in terms of:

- Local pollution: from microparticles, watercourses, etc.);

- Communities: renewable energy sources are necessarily decentralised. Local, municipal control over these sources can empower local communities worldwide (energy security, jobs, etc.).

- Global justice and equity: local control over energy can also, conversely, weaken the fossil fuel giants that have historically been extremely self-serving and anti-democratic forces.

Obviously, keeping the maximum of fossil fuels in the ground and accomplishing a global transition to renewable sources of energy is no panacea. In a growth economy, for instance, an ever-increasing amount of materials will be needed to produce windmills or solar panels, thus requiring ever more extraction of natural resources around the globe (often to the detriment of the local populations and ecosystems). But a radical transformation of the global energy system is a necessary step toward a fairer and less destructive human presence on the planet.

4. Destructive agriculture

(Or: “To solve hunger in the world, we should just use more fertilizers, pesticides, and GMO”)

The so-called “Green Revolution” that spread around the world during the twentieth century might have increased global food security and reduced the prevalence of famines—although this is still a topic of debate. What is quite sure is that by encouraging the mass cultivation of a limited number of crops, and through the massive use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, these practices have notably decreased agricultural and wild biodiversity, and led to global land degradation and soil nutrients depletion, as well as an increase of pests and diseases affecting crops. This, in turn, also pushed farmers to cut down large swaths of forests around the globe to farm new productive lands—and the erosion that ensued exacerbated topsoil losses, leading to further depletion of the ground. As a result, we might have only 60 years of harvests left globally, if things carry on this way. In sum, “past agricultural performance is not indicative of future returns,” according to a recent FAO report.

Besides, high intensity agricultural production is largely reliant on fossil fuels for the production of pesticides and nitrates—not to mention machinery operation. This contributes to the human impact on the climate, and makes phasing out fossil fuels even more difficult. The widespread use of these chemical products has also had severe impact on soil and water pollution, and on human and animal health.

Furthermore, while the “Green Revolution” was largely state-sponsored in the beginning, intensive agriculture is now a market increasingly controlled by multinational corporations such as Monsanto or Bayer (now a single entity), which sell the seeds, the pesticides, and the fertilizers to their clients worldwide. Especially with the advent of seed patenting, leads to increased socioeconomic dependence of farmers upon these corporations for their entire food production process. This is likely to further exacerbate global economic inequalities.

Finally, monocropping tends to be very sensitive to extreme weather events, among other climate-induced impacts.

On the other hand, agroecological practices have been demonstrated to bring yields at least comparable to (if not higher than) those obtained through intensive agriculture, while having a far lighter impact on the soil—and even favouring soil regeneration, since such systems make very little use of chemical inputs such as pesticides or fertilizers. As these practices generally rely on combinations of multiple crops, they are also much more resilient to climate change. Agroecological farming systems also mitigate impacts on climate change, as they produce soil that stores carbon, and their cultivation does not emit greenhouse gases. Other environmental impacts (such as soil and water pollution, etc.) are also minimized, while also boosting agro-biodiversity.

In a word, such systems have numerous advantages over intensive, industrial agriculture—and their yields are not lower. Transitioning toward such new frameworks in both developed and developing countries appears absolutely necessary.

5. Extractivism

(Or: “…and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”)

The “extractivist” mindset can be defined as one that encourages “a resource-depleting, nonreciprocal, dominance-based relationship with the earth—purely one of taking.” [3.Klein, N. This Changes Everything. p.169] In this perspective, ecosystems are but “natural resources,” and people simply “labour” or even a “social burden.”

It was this vision of the world that supported the advance of the industrial revolution, largely based on the extraction of coal, as well as colonialism. As for the modern market economy, it emerged simultaneously with these worldwide phenomena, as an efficient way of allocating mass-produced consumer goods and stimulating their production continuously.

Consequently, the extractivist mindset is part and parcel of both imperialism and the growth economy; indeed, the latter relies (as seen above) on the never-ending extraction of raw materials from the earth. In this view, natural resources are considered “unlimited,” thus negating the existence of planetary boundaries that the human species should not cross, in order to avoid catastrophic tipping points.

In order to enact a global transition to a post-growth economy, relying on stable renewable energy sources instead of the consumption of limited fossil fuels, with more social justice and wealth redistribution worldwide, and in order to stop the massive human-induced biological extinction that is currently unfolding—humanity must phase out of this extractivist mindset.

While it is necessary to ensure that human poverty be eradicated, we must also imperatively recognise that the earth does not exist to be dominated and exploited by mankind, and that other species have as much a right to exist as humanity. Without such a change of mindset, any effort to shift out of the paradigms highlighted above might only be short-lived and shallow, or else accomplished under anti-democratic conditions.

This calls for worldwide education and consciousness-raising campaigns, reaching out to children and adults alike.

***

That’s all for now…

As noted above, please feel free to send any feedback.