異端児 Maverick

I was wondering how it might feel to live within a jikkenchi as one of these people who go against the grain and rage against the dying of the light, these lone wolves and escaped horses. Is there space for them within the Yamagishi Society, where calm discussion is the norm, where nobody should ever get angry? Can they, too, be integrated within this ever-harmonious fabric, and thrive?

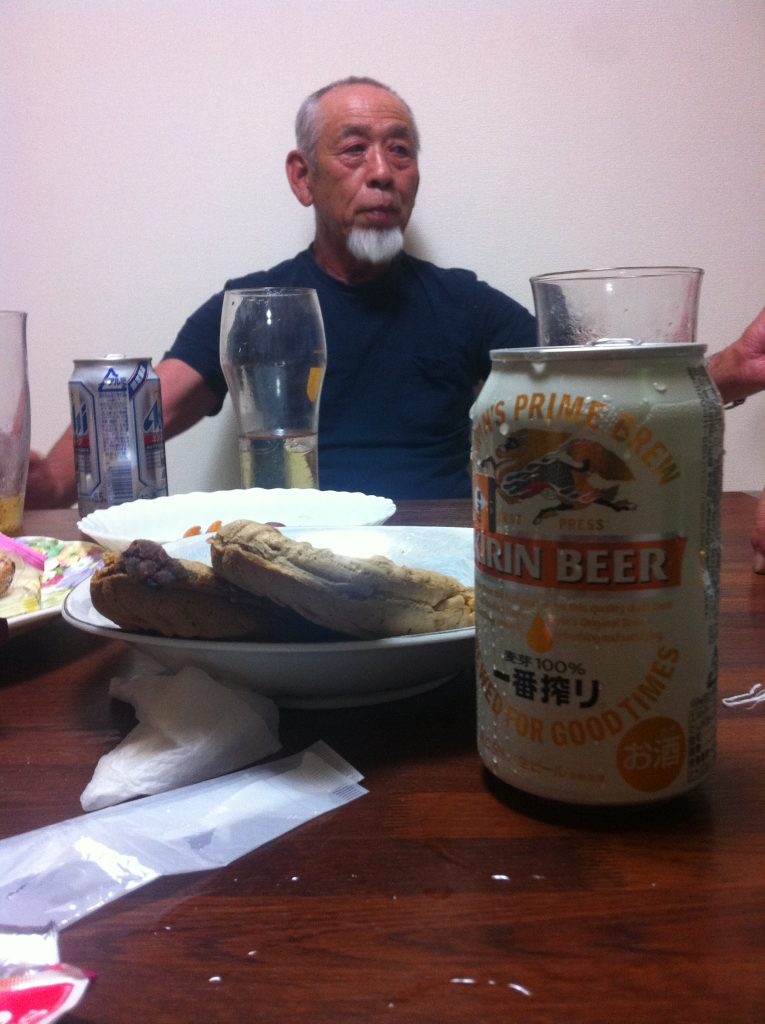

Thankfully, I was able to meet Satō-san. He is 71 years old, and his tall and wiry frame, his wizened face sporting a very Hispanic white goatee cannot but remind me of some vague memories of etchings by Gustave Doré: wearing a suit of armour, he would look very much like a Japanese version of Don Quixote. Not least because he speaks fluent — if exotic — Spanish.

When Satō-san was 23 years old, he got onto an ocean liner and travelled to Argentina. Thereafter, he spent about two decades working as a mechanic in South America, ending up in Columbia, where he met his wife. They went back to Japan together, raised three children, divorced, and she eventually returned to Columbia where she now lives. “But we still have very warm and friendly relations,” he tells me, mentioning how his bilingual children and himself often travel to Columbia for big family gatherings.

It became immediately obvious, when meeting Satō-san, why he found in South America his promised land. When he enters a room, everybody is suddenly aware of his presence: his booming voice, his bouts of open laughter, his way of looking at people straight in the eye when speaking and often touching them on the shoulder to make sure they do listen to his story; in Japan, his raw energy roots people to the spot like rabbits in the headlights of a lorry — nervous, giggling, and incapable (polite as they are) of escaping the long-lasting verbal onslaught; but in Caracas, Havana or Bogotá, he is probably just another friendly, voluble fellow.

Spanish is Satō-san’s only foreign language, and he treasures it immensely as his passport to the world. Sometimes he even seems seized with a compulsive, insatiable yearning for foreignness: upon entering an onsen (hot springs bath) the other day, and chancing upon a trio of bespectacled and middle-aged white people, he pounced onto them and bombarded them with questions on their origins and details of their lives and their trip in the language of Cervantes; the bemused and frightened travellers were from Texas and New Mexico, so of course they couldn’t speak a word of Spanish to save their own lives, but Satō-san made a point of sustaining a nearly five-minute-long, rather one-sided but impossibly jovial conversation with them before the cowering estadounidenses finally managed to flee him. Later on, in a supermarket, he warmly and courteously greeted a Polish woman, complimented her on her elegant dress and hat, and exchanged business cards with her; she didn’t understand the slightest thing he said, but answered him in natural and graceful Japanese.

Satō-san has been a fully-fledged member of the Yamagishi Society for the past 23 years. As such, he has lived and worked in various jikkenchi around the country, mostly taking care of cars and lorries and other types of machinery.

Upon meeting me in Tsuki jikkenchi, overjoyed at having a conversation partner (although certainly not a very fluent one) at his disposal, he immediately started making plans: the following day, he would drive me to various interesting places of his choosing, all around the green and hilly Wakayama Prefecture.

And so we went.

First, we stopped by a jikkenchi that isn’t one: La Hueca de Noe (name unclear), located near Tsuki, is an agricultural community run by people from the Yamagishi Society, following the same basic principles than the other jikkenchi — except that it is not an official Yamagishi community. The reason for this is that its aim is to focus exclusively on organic agriculture, as defined under Japanese law, and therefore be open to foreign WOOFFers come to stay there and work for a while — which is impossible in the “official” jikkenchi, for some reasons still unclear to me. From what I understand, the Yamagishi Society doesn’t produce everything organically, as it would be too constraining. Although people at Yamagishi try their best to reduce their use of pesticides and other chemicals, their production isn’t 100% organic. So in order to be able to use the label “Organic Agriculture,” some Yamagishi members decided to just set up another farm where they would do things their way.

We then drove to Shirahama, a town which, due to its famous seaside onsen, has turned over the years from a charmingly remote village into a concrete-laden, overdeveloped seaside monstrosity. As the museum dedicated to the genius scholar, naturalist and author Minakata Kumagusu — allegedly a speaker of 10+ languages — was closed, Satō-san took me to the wondrous Adobenchaa Waarudo.

For a while, I couldn’t quite understand his explanations regarding what kind of place it was, and the name puzzled me; it was obviously a foreign name in its Japanese rendition — maybe the name of its founder, some strange gaijin (possibly Czech) named Aldo Bencha? “Aldo Bencha Ward,” surely that was the English denomination of that exotic spot we were headed to, and which Satō-san seemed so excited about! Possibly another museum or distinguished mansion of some kind…

It wasn’t until we actually got there and I saw the sign at the entrance that I realised how wide of the mark I was (and how poor at decyphering katakana): the name was, of course, “Adventure World”; it was an animal theme park, famous for its aquatic shows, and for being the only place in Japan where pandas can be bred (all progeny must be sent over to China, obviously).

So I followed Satō-san to two different shows, one featuring otters, dogs, a monkey, a parrot, a hawk, a seal, hulla hoops, and apoplectically cheerful emcees making sure the audience remained a-clapping throughout the show; the other starring dolphins, false killer whales, and exceedingly fit young stuntpeople of both sexes surfing on the backs and nozzles of the former and being launched to inhuman heights by the vigorous and playful cetaceans. We also visited the most depressing penguin vivarium ever, ambled along in earsplitting noise from the loudspeakers everywhere, and sat down to some noodles. Then, over coffee, we talked. Or rather, I listened — doing my best to shift gears in time with Satō-san as he held forth in a steady flow of Spanish and Japanese.

He told me many things about his experience as a member of the Yamagishi Society, many of which confirmed my initial suspicions: it is probably not much easier to live as an eccentric character within this organisation as it is for one to live in the “normal” outside world. To their credit, the other Yamagishi members do seem to have proved rather adaptable and tolerant, overall, of Satō-san’s frequent outbursts of spontaneous energy and bull-in-a-china-shop persona — for instance, on that time when he decided to suddenly leave the jikkenchi where he was staying and move to another one without so much as consulting or forewarning anyone, a move sure to annoy people in a Japanese context.

Another recurrent conversation topic of his was what one could term the “temptation of the leader” within Yamagishi. According to him, there have been times at which some person or other started to act and be considered as the officious leader of the entire Yamagishi Society, against the basic leaderless tenets of the organisation; other testimonies, too, hinted at this having happened. Satō-san also told me of the short-lived splinter groups that gathered around such charismatic figures — demonstrating de facto the Society’s overall resilience to such happenings.

The opinion I’ve often heard from other organisation members on this regard is that one cannot change people’s minds overnight, nor even in the space of a generation or two; if one grows up with the idea that paramount leaders are necessary for a society to function, this notion won’t be discarded easily — and if shared by many, it is bound to be reflected in one way or another within a given social group. “Leaders do not create themselves.” But as far as I could see during my stay, while certain people undeniably carried more clout than others within the Yamagishi Society, they seemed vigilant not to think too much of themselves and sometimes withdrew from decision-making when it didn’t concern them.

Another thing Satō-san mentioned which resonated with me, was that even though everyone is normally entitled to their opinion and free to express it during the kensan meetings, by means of which everything in a jikkenchi is discussed and regulated, in practice people can sometimes find themselves gently coaxed/forced to agree with a decision when it has won over the majority within the group — even though nobody ever votes, and everything is supposed to be agreed on by consensus. I could easily imagine Satō-san often finding himself at odds with the rest of the group on certain issues, and eventually having to give way begrudgingly.

Part of this surely reflects a constant truth in human society — not everyone can have things their way. But in this particular context, to what extent is it due to the Japanese way of seeing the group as reigning supreme over the individual? And to what extent are decisions taken in those kensan meetings following the pattern of informal power structures allowed to exist due to an absence of formal mechanisms (such as voting resolutions and electing people)? I still have no clue.

Finally, as the afternoon and I were growing, respectively, late, and tired of hearing the racket from the roller-coaster train nearby (interspaced with much squawking from unhappy caged parrots), Satō-san got up and suggested we head to an onsen nearby. As we walked back to the car, forgetting even to pay a visit to the famous pandas of Adobenchaa Waarudo, he told me: “Despite everything, it’s not so bad on the jikkenchi, you know.” He has no plans of moving out of it any time soon.

Then we stopped by a seafood market and in keeping with the animal-friendly theme of the day, ate some tasty whale meat sashimi.(*)

= = =

One last thing: in February this year, a manga was published about someone’s experience growing up in a Yamagishi community. It’s enticingly titled I Was Born in Cult Village, and centers on the author’s miserable childhood in the jikkenchi (growing up separated from their parents, going to school without eating breakfast, corporal punishment, etc.) — some of them aspects of the jikkenchi life that have drawn criticism in the past, and led to positive change it seems; others (like corporal punishment) that appear representative of what it must be growing up anywhere in Japan.

Overall, the contents seem a little sensationalized, to say the least. I Haven’t had the time to read much of it yet, but together with Satō-san’s stories, it does tend to show that not everything is as rosy and picture-perfect in these places as it may seem to a starry-eyed outsider like me. The ideal society is still work in progress.

(*) Just kidding… Whale meat isn’t all that great anyway. We had tuna sashimi instead (ha)