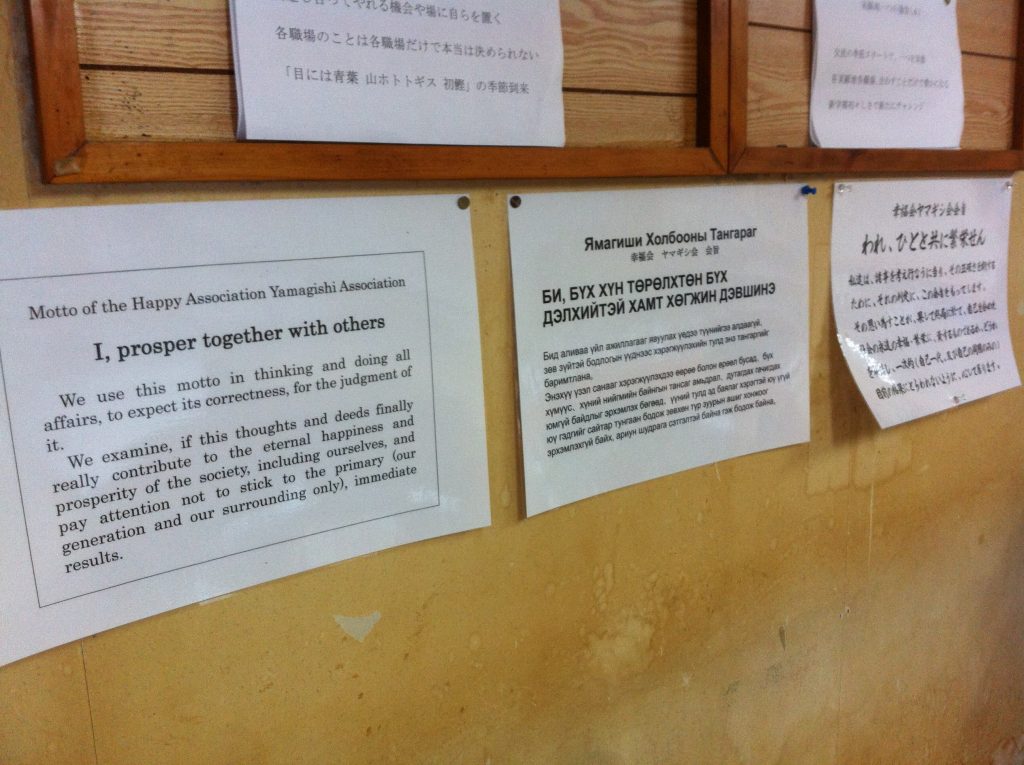

権力 Power

Sign at the entrance of Mutsugawa jikkenchi: “A village where money isn’t necessary, and where life is fun” – “How about we all work together, everyone?”

Alright, here we go… This is going to be a tough one. If you are not a sociologist or political science wonk, it might be a good idea to avert your eyes (although by doing so you’ll miss out on cute pictures of pigs, among other sublime contributions to the Art of Photography).

One of the more mysterious aspects of life in a Yamagishi community, to me, is the way power is allocated or distributed. It’s largely in order to understand more about this that I came here in the first place.

The social structure Yamagishi members strive to create is, in principle, horizontal and leaderless. Each community (jikkenchi) functions to a large extent independently from the others in Japan or abroad; there are no cadres or anyone else whose role is to coordinate the allocation of resources and labour either within a given community, nor between the different communities — at least, no one is supposed to perform this job on a permanent basis (therefore acquiring the same sort of power that cadres monopolised in the ex-USSR or nowadays in China).

And yet, at least some kind of power or decision-making structure is bound to appear in any human group, if only to make things happen; structurelessness does not exist. All the more so in the case of a complex intentional organisation like that of the Yamagishi Association.

How is power allocated within a given jikkenchi, and within the network of communities? Below are my findings so far.

NB: As there are no clear-cut organisational rules governing any jikkenchi — indeed, one of the main credos of the Yamagishi Association, according to what we were told during tokkoh, could be summed up as “nothing is absolutely true, everything can be questioned” — all the information here is only what I’ve been able to gather in my conversations with people, and by observing everyday life situations in which I was involved; but my Japanese isn’t exactly stellar yet (understatement alert!), and the informality of it all coupled with the special Japanese love for hints and elusiveness probably brought about many misunderstandings on my behalf. This is still work in progress.

AT THE JIKKENCHI LEVEL

A jikkenchi can vary in size and complexity.

Tsuki jikkenchi, where I am staying now, focuses exclusively on poultry farming, and only 13 adults work here. No need to devide the workforce into work departments: tasks are distributed informally, as in a big family — the women cook, take care of the kids and the laundry, and prepare the eggs for shipping; the men take care of the hens, harvest the eggs, repair the machines and buildings, cut the grass, etc.

In a small community like Tsuki, power does seem rather equally distributed (although I’m unsure if a woman would be allowed to go cut the grass instead of feeding the kids, but well, this is Japan after all — I’ll come back to gender and other cultural issues later): one’s work schedule and contents can be, and are openly negotiated with the others, especially during the kensan meetings that take place at given tea-break times during the day.

There is clearly someone here who is in a position of relative authority compared to everyone else: Kōzō-san, who was one of the facilitators at my tokkoh. He is only 30-something years old, but he radiates the sort of natural confidence and calm that is the stuff of leaders; he is also very intelligent, and has lived all his life on Yamagishi farms (he was born on one), so he has very intimate knowledge of the way things work around here. He is the guy whose name people mention whenever they mention Tsuki jikkenchi in other communities. I don’t see him giving direct orders, but it is clear he is listened to and influential — interestingly, much more than his elder brother or even his father, who live here too but seem to not have any interest in running the show or participating in meetings.

In Kasugayama jikkenchi, however, over 200 people live and work together to produce fruits and vegetables, pork meat, dairy products, noodles, and more. As a result, work is organised and coordinated in the shape of different shokuba (職場 – departments): Veggies, Pork, Dairy, etc. Other departments include Kitchen, Maintenance, and Administration.

In each shokuba, a representative emerges organically, out of the respect in which people hold them, largely due to this person’s knowledge, experience, and charisma (much in the same way that Kōzō-san emerged as the informal leader of Tsuki jikkenchi): as I was told, “nobody can know everything about everything. The representative is the person we go to when we want to understand more about veggies or pigs, for instance. This person knows their stuff.”

Even though nobody was ever introduced to me as “the guy in charge” in any of the shokuba where I worked at Kasugayama, it was clear from the first tea-break collective gathering who was most listened to, and thus who initiated movement in the group.

Nagami Yuuki, the very informal (read: freewheeling) head of the Kasuga Pig department (center), in the department meeting room

As this person is not elected, their formal authority and responsibility are limited — this “position” should be seen more as halfway between that of a leader and that of a simple contact person. Yet this is the person who will represent his or her shokuba at any of the jikkenchi gatherings where their presence may be necessary (although it seems other members of the department can also attend if they so wish).

However, becoming too much of an expert in one field or another is also recognised as a potential source of power accumulation in the Yamagishi Association (knowledge is power, after all), therefore an experienced member from a given shokuba will normally be encouraged to move to another department once in a while, and thus try their hand at something else. I’m unsure how often exactly this happens, but people seem to be aware that this should take place from time to time.

In a word, decision-making in the jikkenchi is supposed to happen in the most decentralised and bottom-up way possible, never in a centralised and top-down way. This ties in nicely with what people told me about owning/acquiring things.

With these principles in mind, in what way are the activities of the Yamagishi Association coordinated on a national level?

AT THE NATIONAL LEVEL

Each jikkenchi functions primarily by and for itself. But after all, a small community like that of Tsuki can hardly be expected to meet all its needs (especially food-wise!) by its own means, when all it does is breed chickens.

For this reason, the “official” Yamagishi communities throughout Japan (yes, there are also officious communities… I’ll come back to that in a future post!) are integrated within a common network, in order to allow for, among other things:

- the distribution of resources produced throughout the different jikkenchi (more than 90% of the food we eat every day, in Tsuki as in Kasugayama, be it veggies, meat, dairy products, ketchup, pickles, bread, etc. has been produced entirely in one jikkenchi or another, then distributed for free throughout the network);

- the integrated sales of these same products to the outside world, through the Yamagishi web-store and the dedicated local grocery stores managed by Yamagishi members (such as the one in Sakai);

- the distribution of workforce throughout the communities — Yamagishi members, especially younger ones, are often encouraged to gather in other communities than the ones where they are based, in order to help fulfil momentary labour needs (this week, for instance, youngsters are flocking from all around the country to the northern province of Akita, in order to go rice-planting; in the autumn, they might all come back there to help with the apple harvest, etc. Their travel costs are covered by the Yamagishi Association, of course);

- and finally, the coordination of the Yamagishi Association’s interactions with the outside world: To build, or not to build primary schools in the jikkenchi? How to answer media requests and other questions about Yamagishi? (there is a Yamagishi Information Centre in Tokyo it seems) Etc.

My fellow co-worker (and representative?) at the Kasugayama Veggies dept., Miyazaki-san, holding a delicious Yamagishi tomato – poster on the wall of a Yamagishi grocery store in Sakai, Wakayama-ken

Much of this can be taken care of online, especially through Mula-net.com, the main Yamagishi member’s internal information channel (where yours truly has recently had the honour of being featured in an interview).

But naturally, more complex decision-making involving all the communities requires face-to-face interaction. From what I was told, this takes place through regular gatherings of representatives from each jikkenchi. One would imagine these “representatives” could therefore be informally considered the leaders of their respective jikkenchi… Except that one can only act as a representative in those gatherings for up to six months at a time, before being replaced by someone else.

This would mean that Kōzō-san, for example, would not attend these gatherings as the representative of Tsuki jikkenchi all the time, but would let someone else go instead.

In larger communities like Kasugayama, the representative’s designation process is still obscure to me, but it seems he or she is chosen informally by a gathering of the representatives of each shokuba (see above).

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL

Official Yamagishi communities currently exist in Korea, Thailand, Australia, Switzerland and Brazil. There used to be one in California, and another one somewhere in Germany, but they have since then been closed. There is currently talk of a new one starting soon in Taiwan, and perhaps in Mongolia.

Each of these foreign jikkenchi are rather small (no more than 10-20 people), and outside of Korea they were kickstarted largely by Japanese immigrants (or their descendants). There seem to be particularly close links between the Japanese jikkenchi and their Korean counterparts, as could be expected due to the relative geographical proximity. I’m yet to meet anyone who has travelled to the one in Thailand.

As the Yamagishi Association still remains largely Japan-focused, it seems the main links with foreign jikkenchi are on the level of best practice exchanges, and occasional friendly visits. But there isn’t much coordination on a material or human level, as far as I’m aware.

***

So — this is what I know as of now regarding the way the decision-making process is structured in the Yamagishi jikkenchi. This is probably just one tip of the iceberg.

Two questions I’m still curious to work on are:

- How truly egalitarian is this structure? Japan has a knack for often keeping the rules that really govern society hidden behind a distorting surface (the infamous honne/tatemae or ura/omote dichotomies). In other words — does this structure have enough clarity to avoid the well-known “tyranny of structurelessness”? Quote:

As long as the structure of [a] group is informal, the rules of how decisions are made are known only to a few and awareness of power is limited to those who know the rules. Those who do not know the rules and are not chosen for initiation must remain in confusion, or suffer from paranoid delusions that something is happening of which they are not quite aware.

- How does a jikkenchi work outside Japan? In a way, this question is related to the first one. Do people in Switzerland or Australia, for instance, feel the need to establish more openly democratic processes, such as elections, to distribute power equitably within their jikkenchi? Or can they satisfy themselves with the informal Japanese way?

There is still much to be said on the topic, but I suppose this post is already long enough as it is. Hopefully I’ll find more time to write on this soon, including on my encounter with the Spanish-speaking maverick Satō-san (71 y.o.) and what he has to say about his experience within Yamagishism.

As promised, let me end this article on a magnificent example of porcine photography (this is not a reference to any work of George Orwell’s):